An Introduction to opticsinspace.com 🛰️ 🔭¶

Recently I decided to make my own landing page on GitHub Pages. Once I did, I realized that I could buy this domain for ~$0/year so I went for it. It was a good time to have a consolidated web presence I could call my own, and while I don’t have any other long-term plans for this site I’m open to suggestions or collaborations.

Happy Earth Week! 🌍¶

While, as the domain indicates, my primary focus is building optics for use in space I’ve been lucky to engage with all aspects of remote sensing applications. I sincerely believe that this field has the potential to satisfy important personal requirement of mine: leaving the planet a little bit better than my generation found it.

I’m also fortunate to be enjoying a brief sabbatical at Hydrosat and have time for side projects, and will be thinking about our global/(Unless otherwise noted, I will stick to what I know and discuss things from my Seattle-area bubble of the increasingly globalized space industry.) team as we all celebrate Earth Day. Here are couple of videos I’ve found helpful recently in connecting the dots between the technology and the impact it generates:

- Dr. Josh Fisher: The Fate of the Terrestrial Biosphere

- Dr. Chris Boshuizen: SmallSat Symposium Keynote

Some key quotes:

We’re in a golden age of terrestrial remote sensing. We can now see remotely every component of the water cycle, we have great measurements on the carbon cycle, and even nutrient cycle. - Dr. Fisher

Of the key 15 indicators for tracking the volatility of our weather systems and the climate, over half of those can only be collected from space. - Dr. Boshuizen

And a meme to summarize my thinking so far:

Figure 1:You knew there would be memes…

Team Earth 👉⚡👈 Team Space?¶

As Dr. Fisher knows the ins and outs of our biosphere, Dr. “Chrispy” understands what’s possible from satellites of all shapes and sizes. One of the most interesting points from his talk is the migration over the last few years from CubeSats to SmallSats, which offer increased payload mass and a much more flexible form factor. Anyone trying to put big capabilities into small packages understands this shift, but it’s probably worth its own follow-up in the future. (We’ll probably have satellites that move like Luke’s training droid before I get around to that, though…)

There are plenty of technical challenges in merging commercial space capability, especially the “new space” variety, with scientific capability that meets the requirements of a NASA Earth Science mission. More to unpack in the future - for now I’ll drop these worthwhile references:

- Leveraging Commercial Space for Earth and Ocean Remote Sensing, from the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine (NAESM)

- “Space from Scratch” Workshop by Open Geospatial Consortium

- TerraWatch podcast by Aravind:

- Can Space Infrastructure Be Outsourced, with Alex Greenberg of Loft Orbital

- From Concept to Operations How to Build a Satellite Constellation, with John Springmann of Tomorrow.io

- #TeamEarth vs. #TeamSpace, by Alexandria Zeus (requires subscription)

There are a couple of interesting themes that emerge across all of these discussions, posing them as questions:

- What does a space company need to do to differentiate its product enough to be interesting?

- What can a space company not do, and reasonably expect others to fill in, to build and deploy the mission/ system it requires?

Space startups will surely continue to come and go. Answering these questions early might be a good choice for those that want to stick around, even if the answers are refined over time. When developing new missions there is only so much gas in the tank at any point (or “delta-V” as we call it in the space biz), so it is important to think tactically as well as strategically while getting from one gate to the next.

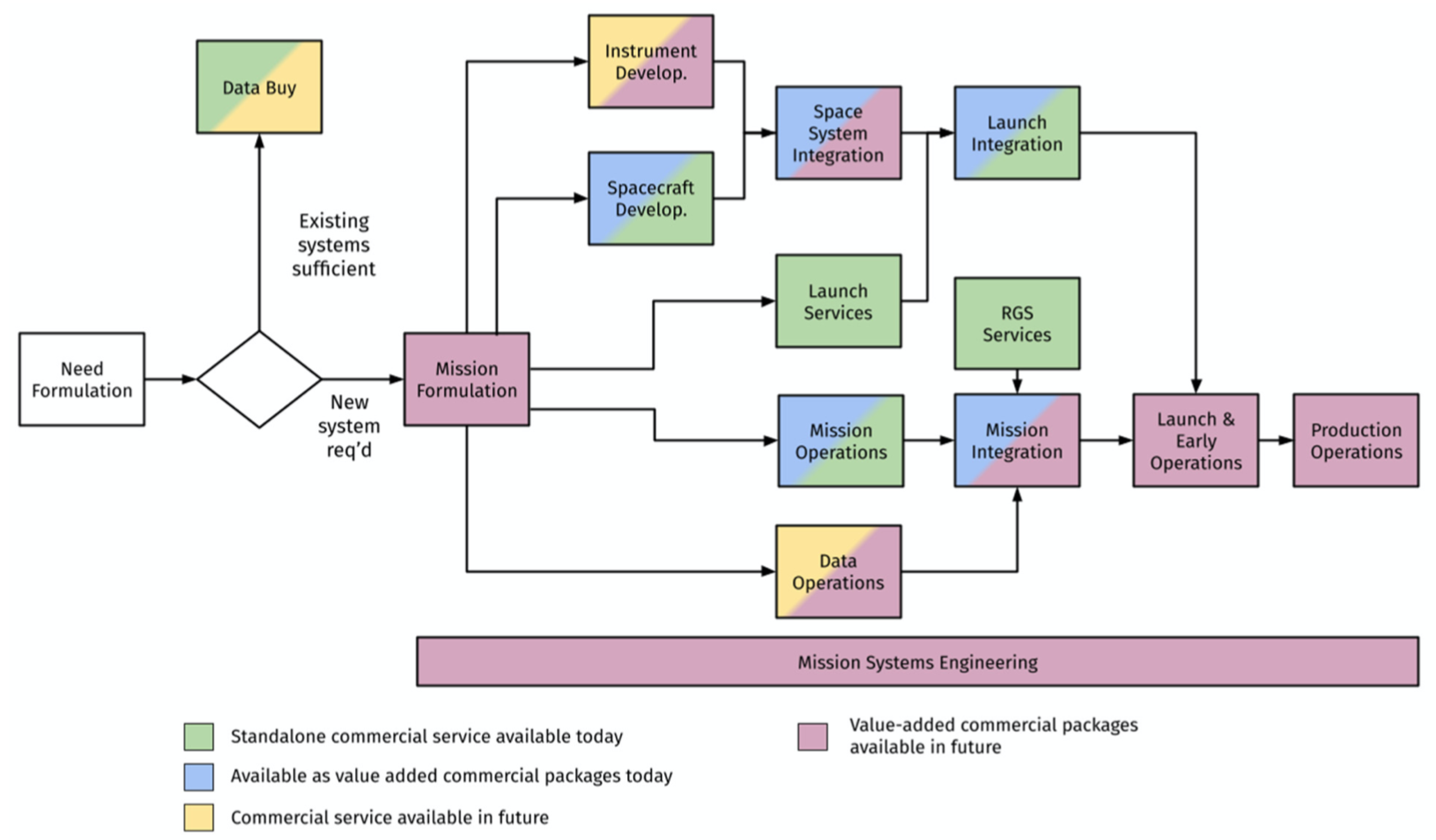

Note that while we often think of NASA missions as having infinitely flexible budgets, the reality is that even they must proceed through stage-gated development cycles. There already exists a proven template to transition research-level hardware, which may or may not use commercial components, to operational science missions. It’s just not one that any given startup has time to follow in its entirety! Putting the pieces together across multi-organizational efforts is becoming increasingly important towards constellation-capable (smaller, cheaper) remote sensing systems.

There is another interesting set of questions that applies at the mission level, rather than defining a company’s entire vision. Mainly, what level of detailed design is required for the spacecraft and how unique are the accommodation requirements of the payload? These questions will ultimately drive the decision between a standalone mission, with any number of purpose-built components or operational needs, and a hosted payload which is meant to integrate with an existing bus and mission design. The current state of affairs is elegantly mapped out in the above NAESM report for both standalone and hosted missions; their high-level flow for standalone missions is shown below.

Figure 2:Standalone mission model & commercial space readiness. (Fig 2.4 in NAESM report.) For the hosted payload version (NAESM Fig 2.5) cuts out custom spacecraft development, and launch is bundled with integration, ground station (RGS), and operations.

I’m the last person to ask about public relations, but the challenges the industry must overcome in this arena aren’t difficult to spot. While there are endless sources of good info that tackle the subtleties of building companies, systems, missions, and even economies to get the job done, this is obviously not what the public is exposed to. At best, the stories of the new space industry are percolated through multi-layered media houses and secondary or tertiary sources used. At worst, every single space startup large or small gets lumped into “billionaires joyriding to space” or assumed to be making vaporware.

The truth is that most startups working on hardware - from entire satellite constellations to spacecraft subsystems - face a huge uphill battle in terms of capital expense and customer traction to hit even meager revenue streams or requisite funding checkpoints. Most of us don’t expect to be cheer-led, but when obtuse characterizations make their way into the public sphere there are real threats of policy change that hinders progress. My hunch is that the next decade of success stories in this industry are already forming the critical partnerships, even if the company doesn’t exist yet, and are willing to weather some storms if they haven’t already. Space and hardware will always be hard, but a wider appreciate for the idea that space tech can help us on Earth could certainly lighten the mood a little.

The most visible asymmetries between new space and “old traditional space” are factory floors, computer-controlled machines, high bays, and cleanrooms. However, there is another asymmetric advantage that hides in plain sight: the inertia of government procurement and established contracting channels at all levels of traditional aerospace. Space startups often bolster their ability to win government contracts, which most need to survive, by filling their boards or federal business units with anyone from former agency heads to procurement specialists. These credentials in turn draw investors, required in the typical case that the C-suite is not already filled with tech billionaires. Closing the loop on relatively steady-state public funding and more agile risk-savvy private capital may be one of the biggest leverage points given the current state of the new space economy.

Space startups often bolster their ability to win government contracts, which most need to survive, by filling their boards or federal business units with anyone from former agency heads to procurement specialists. These credentials in turn draw investors - required in the typical case that the C-suite is not already filled with tech billionaires. Closing the loop on relatively steady-state public funding and more agile risk-savvy private capital may be one of the biggest leverage points given the current state of the new space economy. Continued improvements to procurement process within government is also up there.

Raising capital and developing customer channels are expected with any new venture, none of this is meant to imply that space is special. It is the simultaneous speed, scale, and complexity demanded by the next wave of space missions that drives the need to ramp funding and build partnerships early. The spend needed for a minimum viable product is inevitably larger than a CRM/SaaS company, regardless of risk posture, which makes hitting marks from round to round more difficult.

The risk of space projects can limit investor appetite, just as the tried-and-true mission runners (read: NASA, USGS, USDA for Earth science; various DoD agencies for other stuff) are not known to readily welcome newcomers. Neither funding avenue (private or public) is better than the other, they just operate using different metrics and on their own schedules that must appreciated for successful integration in a multi-year development roadmap. There have been several notable exceptions, and now is a good time to examine how we replicate the conditions that have led to sustaining contracts to up-and-coming space companies.

Reflecting on a Year at Hydrosat 🚰 👨🔬¶

Hydrosat’s differentiated product is thermal band remote sensing data, at a low enough cost point that it can be scaled to a constellation of over a dozen satellites and provide daily global coverage. I’ve had the pleasure to absorb all of the info I can about crop yield forecasts, evapotranspiration models, and irrigation optimization from our data team in Luxembourg and Dr. Fisher, our scientist in charge. We are leaning on a number of partners to support our VanZyl-1 demonstration mission - a hosted payload with Loft Orbital - and eventual constellation, each one filling in critical needs to support an overall measurement system.

Since joining last year, it feels like we have been moving at warp speed as we develop specifications, complete design reviews, and order hardware. As a lean seed-stage startup, the development velocity we’ve been able to achieve brings new surprises every day. We are leveraging a broad network of engineering talent and manufacturing capability across the US and Canada to achieve our goals. There are also lessons being learned from VanZyl-1 that we will surely carry forward to future missions. For example, the more partners we add to the our extended team the more important it has become to monitor our communication overhead! Also, SmallSats can still be a heavy lift.

We will be sharing more in August, at the SPIE conference on CubeSats and SmallSats for Remote Sensing in San Diego. Ad Astra! 🚀